1Former Social Worker, Bal Mandir educational trust

2Senior Technical Office, Kerala State Commission for Protection of Child Rights, Thiruvanthapuram, Kerala.

3Associate Professor, Department of Psychiatric Social Work, NIMHANS, Bangalore, Karnataka

Address for correspondence: Dr Sinu Ezhumalai, Associate Professor, Department of Psychiatric Social Work, National Institute of Mental Health and Neurosciences, NIMHANS, Bangalore. Pin: 560029. E-mail: esinu27@gmail.com

ABSTRACT

Aim: To study the psycho social problems of adolescent girls during menstruation.

Methods: Cross-sectional study was conducted in Chennai.

Descriptive research design was used. Sample size: Sixty students were selected randomly by the teacher from Bhoodhur Govt high school, Sholavaram, Chennai and referred to researchers for the study purpose. Inclusion criteria:Adolescent girls who were aged 13–16 years and attained menarche

Results: Majority (71.7%) of adolescent girls belong to the age group of 14 – 15 years, 68%,12 were in ninth standard. Nearly half of the respondents were using pads (45%) and clothes (42%) as absorbent, majority (65%) preferred to discuss their menstrual problems with mother, 28% with friends about menarche, 7% do not discuss with anyone. Most of them (58%) faced physical problems during menstruation such as premenstrual syndrome (55%), menorrhagia (12%), sleep disturbance (12%), body pain (68%), headache (45%), leg (55%) Majority (67%) had psychological problems such as change in mood (70%) irritability (78%) restlessness, (63%) unstable mood, (58%) feeling stressed). One-third had faced psychosocial problems in terms of unawareness of menarche before the

onset (65%), 10% did not have privacy to change sanitary pads and did not know how to use them, 32% faced restrictions during menarche.

Conclusion: Mental health education of adolescents’ girls is essential to deal with

psycho-social problems related to menstruation.

Keywords: Menarche, School social work, Adolescents girls, Mental health education

Introduction

Menstrual health may be defined as a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being and not merely absence of menstrual problems1. It is essential for improving global public health and achieving sustainable development goals. Psycho-social problems are common during menstruation in adolescent girls. Menstrual problems affect their academic performance, school attendance and social life. Menstrual problems are affective and somatic in nature. Although several studies have reported physical problems faced by adolescent girls during menstruation, however few studies focused on the psychosocial aspects of menstruation. Adolescent girls face significant psychosocial problems during menstruation in terms of access to clean materials, lack of privacy for changing pads, disposal facilities for sanitary napkins, socio-cultural restrictions, less psychological and social support, poor knowledge about managing pain during menses, non-availability of counseling services, and inadequate information on menstruation and its management, no preparation before menarche, menstrual distress, burden and stigma.

Previous studies have reported that adolescents’ girls aged 15 – 19 years felt sick, sad, irritable, and missed school during menstruation2. They were unable to concentrate and pay attention during school hours. Before menstruation, adolescent girls were irritable and depressed, nervous and sad 7 and during menstruation, these problems got aggravated3.

Most girls were scared at the onset of menarche. Other reactions were worry and sadness4. Few college students reported suicidal ideas and death wishes during the pre-menstrual period5. Pre menstrual symptoms, depression, irritability, mood swings, sense of losing control, retention were significantly correlated with students who had suicidal ideas compared to women without suicidal thoughts. There seems to be an association between menstruation and suicide6.

Most common psychological problems reported by adolescents before menstruation were tiredness, anger, headache and irritability, fear, and depression8. Few studies reported psychosocial problems such as pre-menstrual symptoms, sleep disturbances, prolonged bed rest, inability to concentrate on studies, depression, irritability, headache, malaise, fear, anger, tiredness, foul odor, and anxiety, disturbance in daily routine, missed social activity 8,9,10,11,12,13. Young girls with premenstrual symptoms reported insomnia, nervousness, fatigue, headache14 and sleep problems15. Many girls were unable to perform household activities and attend sports. Dysmenorrhea andmenorrhagia increased the risk of school absenteeism among rural girls16. Coital activity is a common cause of many adolescents menstrual problems17. Seeking medical help for menstrualproblems (dysmenorrhea) is very poor among teenage girls18. Dysmenorrhea and menstrual irregularities were linked with dietary habits (eating junk food, eating less) and premenstrual symptoms were related to lack of physical activities19, overweight, eating less, taking junk foods20.

Duration and menstrual cycle regularity were determined by factors such as socio demographicprofile, psychosocial stress, disturbed sleep, arduous physical exercise, diet 21,22,23. Various studies have reported increased stress during menstruation is the strongest predictor of menstrual irregularities. Unhealthy lifestyle as well contributes to menstrual abnormality. Increased stress was associated with disturbed sleep during menstruation24. Poor knowledge, inadequate information, less awareness about menstrual problems, exclusion and shame lead to misconceptions and unhygienic practices during menstruation among teenagers. Restrictions in social interaction, self-medication, lack of knowledge about unhealthy coping with menstruation were problems experienced by adolescent girls in low andmiddle-income countries25. Most studies found that girls were restricted from school activity and physical activities such as play, traveling, attending social gatherings, functions, festivals, marriages, worship, food restrictions, entering a temple, kitchen, others house, doing household work, taking a bath, attending school, touching people and pooja materials 2,26,27,28,29,30. Restriction in activity varies from culture and region. In some parts of southern Indian villages, girls were even not allowed to enter their own house, and they were asked to sit and take rest in the house entrance duringthe menses. Girls were considered dirty and impure during periods. There is an association between educational level, activity restrictions and practice regarding menstruation31.

Socio-cultural practices regarding menstruation depend on girls’ education, attitude, family environment, culture, and belief 32. Adolescent girls in slum areas face multiple restrictions (such as staying out of the house and separation from family members, not touching anyone), not aware of menarche prior to menstruation, do not know the cause of bleeding, and organ where bleeding occurs, disposing the pads open area, using common toilet for changing pads33. Urban and rural girls were aware of menstruation before attainment of menarche34. In urban girls, the mother was the main source of information about menstruation, whereas it was a teacher in the rural areas. Regarding onset of menarche, urban girls tend to attain puberty earlier than rural girls. Girls from upper socioeconomic status have lower mean age at menarche in rural and urban areas and higher mean age was found in urban girls involved in rigorous sports35. Cleaning of external genitalia was more satisfactory in urban than rural area36.

Premenstrual symptoms were more in urban than rural girls, whereas school absenteeism due to menstrual problems were more in rural girls. Menstrual practices were better in urban girls as compared to rural girls. More urban girls use sanitary pads than rural girls37. There is a difference between rural and urban girls in terms of awareness about menarche and menstruation, type of absorbent used, method of disposal of the same, cleaning of external genitalia. Majority of rural and urban girls feel no need to seek help from a doctor for menstrual problems and do not get counseling for menstrual hygiene from professionals and most of them were counseled by their mothers regarding menstrual hygiene. Most of them felt depressed and scared about their bleeding and changes in body during menses. Most of the girls perceive that restrictions should not be imposed on them during menstruation38.

There were two systematic reviews and meta-analyses on menstrual hygiene among adolescent girls in India. Van et al (2016)39 reviewed 138 studies published from 2000 to 2015. Outcome measures were menarche awareness, type of absorbent used, disposal, menstrual hygiene, restrictions, and school absenteeism. Results revealed that half of them were aware about menarche, many faced restrictions, inappropriate disposal of absorbent, one-fourth were absent from school during periods, one-third had facilities in schools to change pads, half of them had toilets at home to change absorbent. Rural girls faced scarcity of water, non-availability of toilet,bathing space, lack of privacy and bathing restrictions during menses. Systematic review showed that most were surveys, few used mixed methodology and experimental design. Half of the studies were school based and one-third were community based. More studies were from south India.

A systematic review of 183 out of 1125 studies published to 2019 on menstrual hygiene preparedness among Indian schools. Results revealed that less than half of them were aware of menarche, teachers were fewer common sources of information and half of the schools had separate toilets for girls40.

Another systematic review on effects of Menstrual Hygiene Management (MHM) on health and psychosocial outcomes revealed that poor MHM is associated with reproductive tract infections. There is good evidence that educational interventions improve MHM practices and reduce social restrictions41.

Literature Gap

Most of the studies were focused on awareness, attitude, beliefs, conception, cultural aspects, determinants, experiences, general health, hygiene, help-seeking behavior, knowledge, perceptions, practices, prevalence, problems related to menstruation. Most of the Indian studies were school-based, and very few were community-based. Several studies focused on adolescent girls in rural and urban areas about menstruation, though urban studies out numbered. Studies on out-of-school adolescents regarding menstruation and intervention studies are less. The majority of studies focused on menstrual patterns, practices and problems. There were no randomized controlled studies on intervention related to menstrual hygiene. No Indian studies have used standardized instruments to report the problems related to menstruation, preparedness, menstrual hygiene management.

There are no studies in India which focused explicitly on psychosocial problems of adolescent girls during menstruation. Therefore, the present study was carried out.

Materials and Methods

Descriptive research design was used. Universe: Study was conducted in Govt high school, Bhoodhur village, Sholavaram Block, Thiruvallur District, Tamil Nadu, among adolescent girls studying in 8th, 9th 10th Std. Sample: 60 girl’s students aged 13 – 16 years and attained puberty who showed their readiness to participate in the study were selected randomly by the teacher and referred to researchers. Tools for data collection: Semi-structured interview schedule consists of socio-demographic factors (9 items), physical problems (3 items), psychological problems (7 items), psychosocial problems of adolescent girls during menstruation (5 items). Interview schedule was used to collect data. Statistical Analysis: Frequency, percentage and Chi square test were used for data analysis. Ethical clearance was obtained from the Institute ethics committee. Oral informed assent was obtained prior to data collection from the girl students. Adolescent girls were briefed about the study before collecting data. Written permission for the study was obtained from the school institution head.

Results

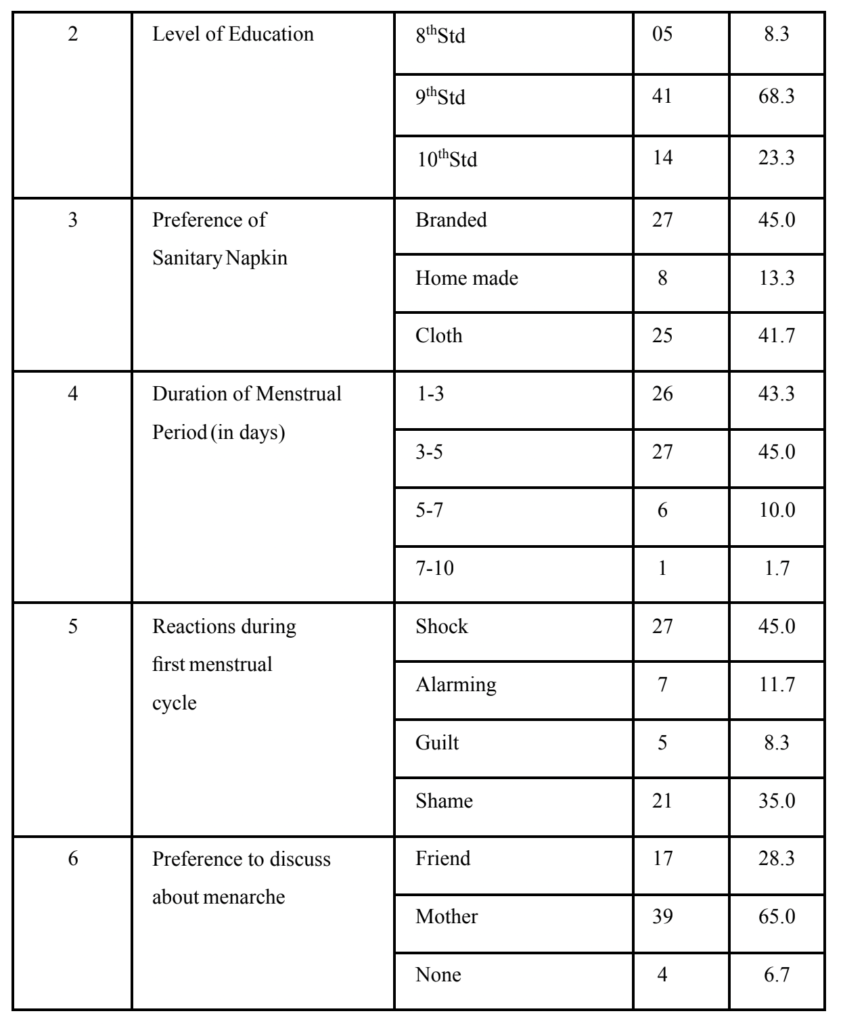

Table 1: Profile of Adolescent Girls

Table 1 shows the majority of the adolescents (71.7%) belong to the age group of 14-15 years in the study, 68% of them were in 9th Grade. Nearly half of the (45%) respondents felt it was convenient to use branded items and few of the (13%) respondents felt it was convenient to use home-made items. Nearly half of the (45%) respondent’s menstrual cycle lasted for 3-5 days, (43%) of respondents had 1-3 days. Nearly half of them (45%) felt shocked during their first menstrual cycle, 35% of the respondents felt shame during menarche. Majority of them (65%) try to discuss their rapid changes with their mother.

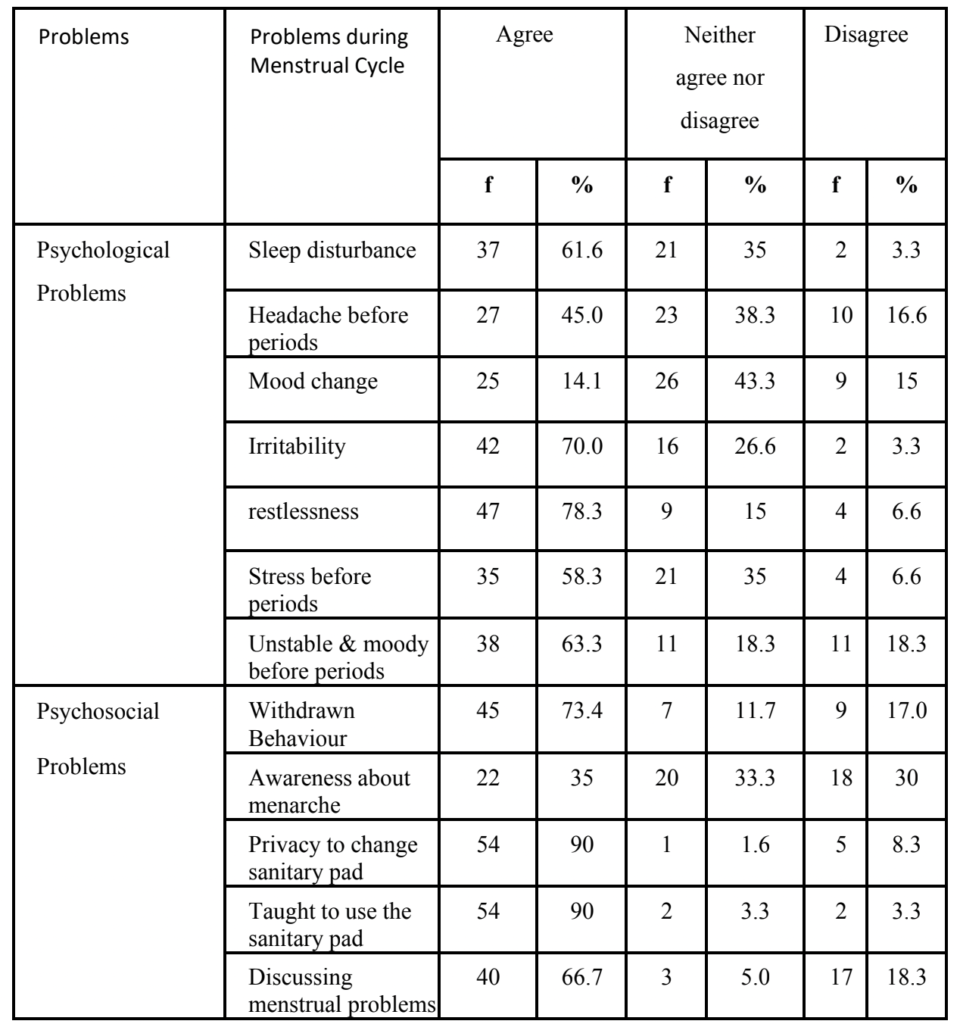

Table 2: Psychosocial Problems faced by adolescent girls during menstruation

Table 2 shows that majority (61.6%) of the respondents agreed that they had sleep disturbance during menstrual cycle and 45% had headache before menstrual cycle, majority (61.6%) of them had lower abdominal pain and (68.3%) had back pain before menstrual cycle. Table 2 also indicates that nearly half of them (43.3%) get mood changes during the menstrual cycle and 70% of respondents felt irritated. 78.3% felt restless during the menstrual cycle. More than one-third of them (39%) had stress before the menstrual cycle and 63.3% felt moody & unstable during every menstrual cycle. One-third of them reported that (35%) they were aware of menarche before the onset. Vast majority of them (90%) agreed that they had privacy to change the sanitary pad and they were taught how to use the sanitary pad. Majority of the respondents (68.3%) moved freely with others during the menstrual cycle.

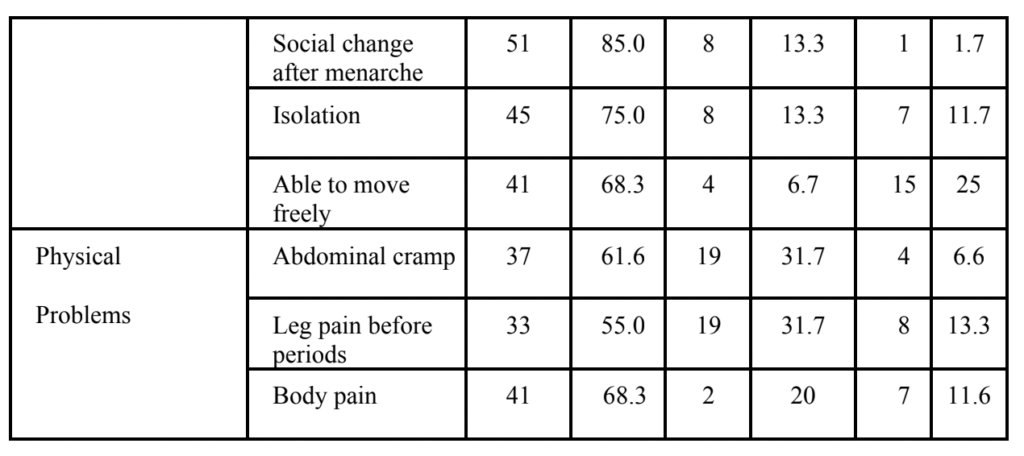

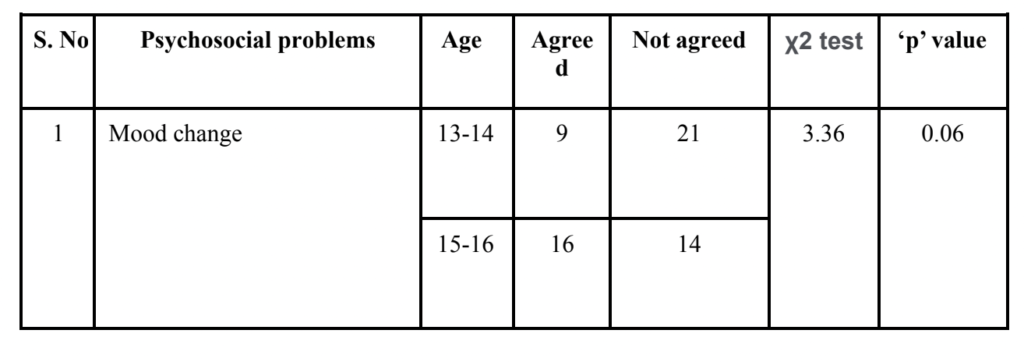

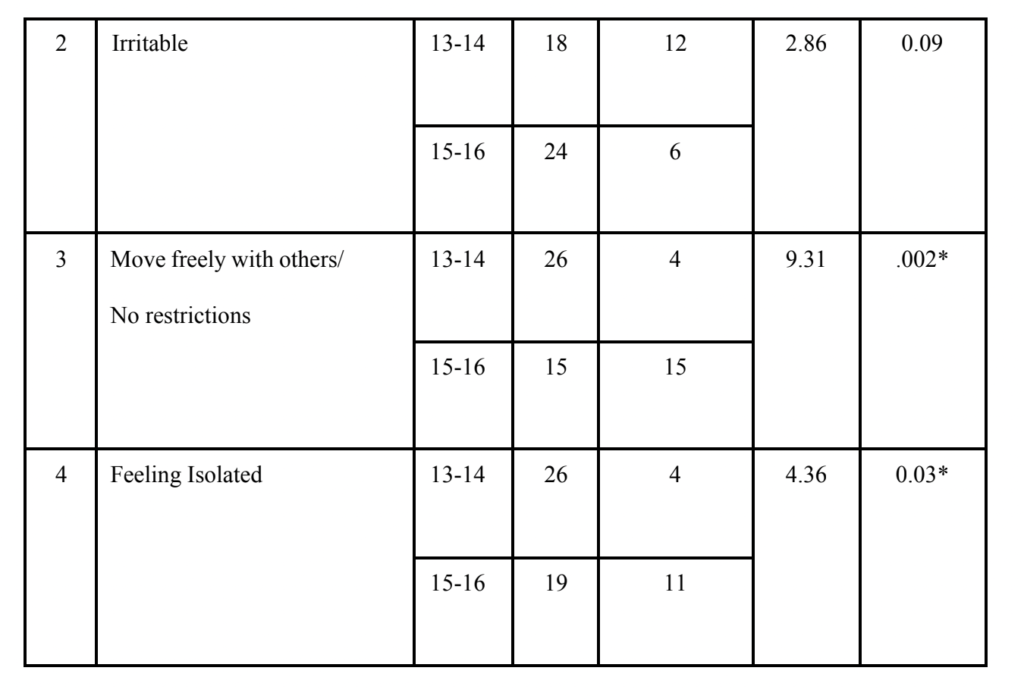

Table 3: Age differences in psychosocial problems of adolescent’s girls

*Significant at p <0.05 level

Table 3 shows age difference in psychosocial problems and coping patterns of adolescent girls during menstruation. Chi-square test revealed that young girls aged 13 – 14 years were able to move freely with others (χ2= 9.31, p=0.02), and the same time they feel more isolated (χ2= 4.36, p=0.03) than girls aged 15- 16 years during periods.

Discussion

Present study showed that more than one-third of girls (35%) belong to 14 -15 years of age respectively. Similar findings were reported by Reddy et al8. Present study showed that 58% of them reported physical problems. Before the menstrual cycle, 45% had headache, 61.6% lower abdominal pain and 68.3% had back pain. In this study, more than one-third of them (39%) had experienced stress before the menstrual cycle and 52% of the girls had pre-menstrual syndrome. Most girls felt restless and irritable, unstable mood and stress during menstruation. These findings were consistent with previous study findings where the majority of girls had irritability during menstruation [2, 7]. Nearly one-fourth of them were embarrassed by pubertal changes and felt shame and guilt30, scared, shy, and sad during menarche31. During the first day of menstruation, girls report psychological problems such as nervousness, poor concentration, sadness, irritability, excitement.

Present study showed that about two-third of the adolescents were unaware of menarche before the onset. This finding is inconsistent with previous studies 8,10,26,31,28,42,43. There is a significant finding from the study that 90% of the respondents did not have a problem with regard to privacy to change the sanitary pad. This finding was in contrast to earlier studies where they reported that most of the children do not have adequate privacy and fully covered toilet facilities at school and at home to change the pad27.

Noteworthy finding from the study is that two-third of the respondents did not have restrictions in physical activity and they were allowed to move freely during menstruation. This finding was contradictory to other study findings that almost all of them were practicing at least one kind of taboo related to menstruation31.

Reasons for restriction in physical activities could be because of the fact that there is loss of blood when they are involved in physical activity such as running and manual labor would cause more bleeding. To prevent the heavy loss of blood above restrictions might be imposed on girls. However, restrictions on touching others, playing games, entering temples, others house traveling and attending social functions do not have any scientific basis. Another reason could be to avoid discomfort in such places and activities these restrictions might be practiced. Though, these restrictions have some benefits in terms of avoiding discomforts during menses. However, in most of the places, these restrictions were enforced blindly on adolescents. These restrictions can be advised, nevertheless cannot be imposed. Few adolescent girls use pills to delay the menses in order to attend marriages, religious ceremonies, festivals, examinations and outings8. Current study showed that 90% of girls were taught how to use the sanitary pad. Out of which nearly half of them (45%) were using napkins and 42% were using clothes as absorbent. Majority of girls had good knowledge about menstrual hygiene in Udupi taluk46.

Good menstrual hygiene was more among those whose mothers were literate10, properly disposed of. Nearly half of them knew about using pads out of which only 11% were using pads, 43% were using old clothes as absorbent27. Majority were using home-made pads in the rural part of East Delhi28. Most of the slum girls used old clothes, very few used pads and 1% did not use anything during the menstrual period. Present study showed only 13% were using home-made absorbent. Majority of girls used soap and water to clean their genitalia 27,43.

In India, across cultures most families enforce restrictions during menstruation. Several studies have reported that adolescent girls were restrained from certain physical activities such as household work, attending social functions, worshiping, touching people and pooja materials, entering temples, kitchens, playing outside, traveling and taking baths. Majority of the people practice some sort of taboo during menstruation and half of them avoid holy places, religious functions and few were restricted from kitchen work44. Some peculiar misconceptions were widely prevailing such as that placing broom sticks, neem leaves, footwear around the menstruating girl wound prevents the entry of evil spirits, excessive sweet intake leads to heavy bleeding, menstrual blood is dirty, and sleeping on bed is prohibited during menstruation45.

Hygiene during menstruation is of utmost importance in order to prevent Reproductive Tract Infections (RTI). In India, poor menstrual hygiene is one of the prime reasons for high prevalence of RTI’s among adolescents and their sexual health needs mostly remain unaddressed. To address this issue, the Indian government announced a new scheme to provide subsidiary napkins to rural adolescent girls.

There is a need to educate and make them aware about the environmental pollution and health hazards associated with disposable absorbents. Awareness should be created to emphasize the use of natural reusable sanitary products. Banana Fiber Pad (BFP) was highly feasible and acceptable in rural and urban adolescent girls during covid-19 pandemic. Adolescent girls were satisfied with the banana fiber pad in terms of comfort and leakage. The microbial load on a 3- year reused BFP was found to be similar to an unused47.

Strengths of the study

This study is first of its kind in India which examined the psychosocial problems of adolescent girls during menstruation.

Limitations of the study

During the study period the researcher approached private schools to conduct the study in and around Chennai. Private schools were not permitted to conduct the study. Hence, the researcher was unable to compare the psychosocial problems faced by adolescent girls in private schools and government schools in urban areas. The study did not use any standardized questionnaire to assess their physical and psychosocial problems. The study findings cannot be generalized to the other population due to limited sample size.

Implications for School Mental Health Education

School Social Workers have a vital role in imparting awareness about menstruation and Menstrual Hygiene Management. Awareness programmes can be delivered through Group Work mode. Knowledge, awareness and dealing with menstrual problems can be covered under menstrual health and life skill training. Following information can be specifically addressed during the programme. Average age at onset of menarche, normal duration of menses, menstrual cycle, pre-menstrual syndrome, common menstrual disorders, body mapping, secondary sexual characteristics, cleaning the genitalia with soap and water, changing the sanitary pad 3–4 times a day according to the need, clarifications about myths and misconception about menstruation, teaching them how to use sanitary pads and proper disposal of pads.

References

1. Hennegan J, Winkler IT, Bobel C, et al. Menstrual health: a definition for policy practice, and research. Sex Reprod Health Matters. 2021;29(1):1911618.

2. Goel MK, Mittal K. Psycho-social Behaviour of urban Indian adolescent girls during menstruation. AMJ 2011; 4(1): 48-52.

3. Patil M, Angadi M. Menstrual pattern among adolescent girls in rural area of Bijapur. Al Ameen Journal of Medical Sciences. January 2013; 6(1):17-20.

4. Srinivas DK, Ghattargi CH. Perceptions and practices regarding menstruation: a comparative study in urban and rural adolescent girls. Indian J Commun Med 2005; 30: 33-4.

5. Chaturvedi SK, Chandra PS, Gururaj G, Pandian RD, Beena MB. Suicidal ideasduring premenstrual phase. J Affect Disord. 1995: 34(3); 193-9.

6. Dogra TD, Leenaars AA, Raintji R, Lalwani S, Girdhar S, Wenckstern S, et al. Menstruation and suicide: an exploratory study. Psychol Rep 2007;101(2):430-4.

7. Agarwal AK, Agarwal A. A study of dysmenorrhea during menstruation in adolescent girls. Indian J Community Med 2010;35(1):159-64.

8. Reddy PJ, Usha Rani D, Reddy GB, Reddy KK. Reproductive health constraints of Adolescent school girls. The Indian Journal of Social Work, 2005; 66

(4):431-441.

9. Padmavathi P, Sankar R, Kokilavani N. A Study on the Prevalence of Premenstrual Syndrome among Adolescent Girls in a Selected School at Erode. Asian Journal of Nursing Education & Research. July 2012;2(3):154.

10. Ray S, Dasgupta A. Determinants of menstrual hygiene among adolescent girls: a multivariate analysis. National Journal of Community Medicine. April 2012; 3(2):294. 11. Sharma A, Taneja DK, Sharma P, Saha R. Problems related to menstruation and their

effect on daily routine of students of a medical college in Delhi, India. AsiaPac J Public Health. 2008;20(3):234-41.

12. Sharma P, Malhotra C, Taneja DK, Saha R. Problems related to menstruation amongst adolescent girls. Indian J Pediatr. 2008;75(2):125-9.

13. Singh MM, Devi R, Gupta SS. Awareness and health seeking Behaviour of rural adolescent schoolgirls on menstrual and reproductive health problems. Indian J Med Sci 1999; 53: 439-443.

14. Arafa, A., Mahmoud, O., Abu Salem, E. et al. Association of sleep duration and insomnia with menstrual symptoms among young women in Upper Egypt. MiddleEast Curr Psychiatry 27, 2 (2020).

15. Gupta R, Lahan V, Bansal S. Subjective sleep problems in young womensuffering from premenstrual dysphoric disorder. N Am J Med Sci. 2012:4;593–595.

16. Ravi R, Shah PB, Edward S, Gopal P, Sathiyasekaran BWC. Social impact of menstrual problems among adolescent school girls in rural Tamil Nadu. Int J Adolesc Med Health. 2017: 24;30(5).

17. Greydanus DE, McAnarney ER. Menstruation and its disorders in adolescence. Curr Probl Pediatr. 1982 Aug;12(10):1-61.

18. Yucel G, Kendirci M, Gül Ü. Menstrual characteristics and related problems in 9-to 18- year-old Turkish school girls. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol.

2018;31(4):350-355.

19. Negi P, Mishra A, Lakhera P. Menstrual abnormalities and their association withlifestyle patterns in adolescent girls of Garhwal, India. J Family Med Prim Care.2018;7(4):804- 808.

20. Vani K R, et al. Menstrual abnormalities in school going girls – are they related todietary and exercise patterns? J Clin Diagn Res. 2013;7(11):2537-40.

21. Rafique N, Al-Sheik MH. Prevalence of menstrual problems and their associationwith psychological stress in young female students studying health sciences. Saudi Med J. 2018; 39:67–73.

22. Singh R, Sharma R, Rajani H. Impact of stress on menstrual cycle: A comparison between medical and non-medical students. Saudi J Health Sci.2015; 4:115. 23. Kansal S, Singh S, Kumar A. Menstrual hygiene practices in context of schooling: A community study among rural adolescent girls in Varanasi. Indian J Community Med. 2016; 41:39–44.

24. Jha N, Bhadoria AS, Bahurupi Y, et al. Psychosocial and stress-related risk factors for abnormal menstrual cycle pattern among adolescent girls: A case-control study. J Educ Health Promot. 2020; 9:313.

25. Chandra-Mouli V, Patel SV. Mapping the knowledge and understanding of menarche, menstrual hygiene and menstrual health among adolescent girls in

low- and middle-income countries. Reprod Health. 2017 Mar 1;14(1):30.

26. Karkada E, Jatanna S, Abraham S. Menstrual beliefs and practices among adolescent girls in rural high schools of South India. International Journal of Child & Adolescent Health, July 2012;5(3):317-323.

27. Dasgupta, A., & Sarkar, M. (2008). Menstrual hygiene: How hygienic is the adolescent girl? Indian Journal of Community Medicine, 33(2), 77–80.

28. Nair P, Grover VL, Kannan AT. Awareness and practices of menstruation and pubertal changes amongst unmarried female adolescents in a rural area of East Delhi. Indian J Comm Med, 2007; 32: 156-157.

29. Kavitha V. Reproductive health and hygiene among adolescents. Language in India. 2012;12(2):293.

30. Ramadugu S, Ryali V, Srivastava K, Bhat P S, Prakash J. Understandingsexuality among Indian urban school adolescents. Ind Psychiatry J 2011;20:49-55

31. Udgiri R, Angadi MM, Patil S, Sorganvi V. Knowledge and practices regarding menstruation among adolescent girls in an urban slum, Bijapur. J Indian Med Assoc 2010;108(8):514-6.

32. Kumar A, Srivastava K. Cultural and social practices regarding menstruation among adolescent girls. Soc Work Public Health. 2011;26(6):594-604.

33. Deshpande TN, Patil SS, Gharai SB, Patil SR, Durgawale PM. Menstrual hygieneamong adolescent girls – A study from an urban slum area. J Family Med Prim Care. 2018;7(6):1439-1445.

34. Deo DS, Ghattargi CH. Perceptions and practices regarding menstruation: a comparative study in urban and rural adolescent girls. Indian J Community Med. 2005; 30:33–4. 35. Dambhare DG, Wagh SV, Dudhe JY. Age at menarche and menstrual cycle pattern among school adolescent girls in Central India. Glob J Health Sci. 2012 Jan 1;4(1):105- 11.

36. Paria B, Bhattacharyya A, Das S. A comparative study on menstrual hygiene among urban and rural adolescent girls of west bengal. J Family Med Prim Care. 2014;3(4):413-417.

37. Thakre SB et al. Urban-rural differences in menstrual problems and practices of girl students in Nagpur, India. Indian Pediatr. 2012 Sep;49(9):733-6.

38. Choudhary N, Gupta MK. A comparative study of perception and practices regarding menstrual hygiene among adolescent girls in urban and rural areas of Jodhpur district, Rajasthan. J Family Med Prim Care. 2019;8(3):875-880.

39. Van Eijk AM, Sivakami M, Thakkar MB, Bauman A, Laserson KF, Coates S, Phillips Howard PA. Menstrual hygiene management among adolescent girls in India: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open. 2016 Mar 2;6(3): e010290.

40. Sharma S, Mehra D, Brusselaers N, Mehra S. Menstrual Hygiene Preparedness Among Schools in India: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of System-and Policy-Level Actions. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020 Jan 19; 17(2): 647

41. Sumpter C, Torondel B. A systematic review of the health and social effects ofmenstrual hygiene management. PLoS One. 2013;8(4):e62004.

42. Prasad BG, Sharma P. A study on menstruation of medical college girls atLucknow. J ObstetGynaecol India 1972; 22: 690-4.

43. Shanbhag D, Shilpa R, D’Souza N, Josephine P, Singh J, Goud B. Perceptions regarding menstruation and Practices during menstrual cycles among high schoolgoing adolescent girls in resource limited settings around Bangalore city, Karnataka, India. International Journal of Collaborative Research on Internal Medicine & Public Health (IJCRIMPH). July 2012;4(7):1353-1362.

44. Ahuja A, Tewari S. Awareness of pubertal changes among adolescent girls. J Fam Welfare. 1995; 41:46–50.

45. Rajkumar et al. Beliefs about menstruation: a study from rural Pondicherry. Indian Journal of Medical Specialties 2011;2(1):23-26.

46. Rao R, Lena A, Nair N S, Kamath V, Kamath A. Effectiveness of reproductive health education among rural adolescent girls: A school-based intervention study in Udupi Taluk, Karnataka. Indian J Med Sci 2008; 62:439-43.

47. Achuthan K, Muthupalani S, Kolil VK, Bist A, Sreesanthan K, Sreedevi A. A novel banana fiber pad for menstrual hygiene in India: a feasibility and acceptability study. BMC Womens Health. 2021 Mar 26;21(1):129.