Megha Rupa, Ahil, Uma Hirisave, Jayashree Ramakrishna

1 – Clinical Psychologist, Victorian Counseling and Psychological Services, Victoria 3001.

2 – PhD Scholar, Junior Consultant, Department of Clinical Psychology, NIMHANS

3 – Professor, Department of Clinical Psychology, NIMHANS

4 – Former Professor and Head of the Department of Mental Health Education, NIMHANS

Address for Correspondence: Megha Rupa, Clinical Psychologist, Victorian

Counselling and Psychological Services, Victoria 3001

E-mail: megharupa07@gmail.com

ABSTRACT

Background of The Study: Normative misbehaviours such as noncompliance, temper tantrums, and aggression can be stressful for parents. While these misbehaviours may disappear in the course of development, they may put children at risk for psychopathology if not handled sensitively. While parent management training is proven to be an evidence-based treatment option, it is important to develop innovative and effective ways of disseminating it to parents in

need. This paper presents the development of parent-training videos to impart parent management training.

Methods: The study was carried out in two stages: the needs assessment stage and the video development stage. In the needs assessment stage, the sample size was 34 parents, and the tools used were the Parenting Stress Index and a semi-structured interview. Data collection was carried out from parents in the community until data reached saturation, and was subjected to content analysis. In the video development stage, a total of 11 child actors and 14 parent actors volunteered to act in the videos. The tools used were a screenplay, video shooting equipment, editing software, and an expert feedback form. A total of 14 videos were shot. Descriptive statistics and inductive content analysis were carried out.

Results: The findings will highlight challenges to parenting within a rapidly changing socio-cultural milieu, and the steps involved in developing parent-training videos for child behaviour problems as a preventive and promotive measure Keywords: Parent-training videos, children, Behaviour problems

Introduction:

Normative misbehaviours such as non-compliance, temper tantrums and aggression can be stressful for parents. While these misbehaviours may disappear in the course of development, they may put children at risk for psychopathology if not handled sensitively. The major hazards to development in children are overly strict discipline, over-protection, excessive demands or competition and persistent failure resulting in feelings of inferiority, inadequacy and incompetence. [1]

Parenting in contemporary India can be conceptualized as striving for a delicate balance between deep-rooted Indian traditional notions of child rearing, and new challenges within a rapidly changing socio-economic milieu. There is a change in the lifestyle of urban women, role strains on mothers, disappearance of the joint family system, excessive distraction and increasing rates of divorce, to name a few of the complexities. Despite the shift from exclusivity to interchangeability in parenting roles, mothers continue to take on primary responsibility for the care of young children in India. [2]

Parent Management Training (PMT) is proven to be an evidence-based treatment option. Numerous studies have demonstrated that videos are superior to written materials, lectures, live modelling, or rehearsal. [3,4] There are few parents training videos available for parents of children with Behavioural disturbances, for parents of children with special needs like Autism, Intellectual Developmental Disorder etc. [5,6,7,8] Indian literature on parenting and parenting intervention explicitly recommends the use of videos in parent training due to their well-documented advantages. [2,9,10] The paper proposes to make a small beginning to develop parent-training videos for the first time in the Indian setting, as per published literature till 2020.

Materials and Methods:

The study was carried out after obtaining approval from NIMHANS ethics board. The study was carried out in two stages: Needs assessment stage and Video development stage. Written informed consent was obtained from the participants (Principals of schools, pediatricians, general physicians, parents, children and actors) across both stages of the study. Limits to confidentiality of the information elicited were explained. Participants were informed that there were no tangible benefits for participation in the study and that they could withdraw from the study at any point of time.

Needs assessment stage:

Sample:

Snowball sampling was used to contact parents from the community for the study. Parents of three to eight years old children who reported stress in the role of parenting over and above other life stressors were included. Parents with a diagnosable psychiatric condition (currently symptomatic) or having a disabling physical illness and children with diagnosable psychiatric, neurological or prolonged physical illness/ disabilities were excluded. Parents were either directly recruited or recruited using schools or pediatricians as entry points. The final sample size recruited was 34 parents (five father- mother dyads and 24 mothers alone). Information about 33 children aged between three and eight years was obtained. Data was collected until problem Behaviours derived from interviews reached saturation. Parenting suggestions were offered to parents who requested the same. For parents requiring further help, referrals were made to help them obtain professional guidance.

Tools:

Screening tools:

● Preliminary two question interview: This was prepared for the study, to establish whether a given parent experiences difficulty in handling any of the child’s Behaviour problems in the last six months, over and above other difficulties, if any. Only parents who reported ‘yes’were included in the study.

● Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview version 6.0 (M.I.N.I. 6.0). [11]

The M.I.N.I. is a short, structured psychiatric interview developed for DSM-IV and ICD-

10 psychiatric disorders. The M.I.N.I has been used by mental health professionals and health organizations in more than 100 countries.

With an administration time of approximately 15 minutes, it elicits all the symptoms listed in the symptom criteria for DSM-IV and ICD-10 for 24 major Axis I diagnostic categories, one Axis II disorder and for suicidality. In the present study, M.I.N.I. 6.0 was used to exclude parents who are currently symptomatic with diagnosable psychiatric disorders.

The Strengths and Difficulties questionnaire. [12] The Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) is a brief Behavioural screening

questionnaire for children aged between 3-16 years developed by Goodman in 1997. It has five subscales: hyperactivity, emotional symptoms, conduct problems, peer problems and pro-social Behaviour scale. As a screening tool in the current study, the parent version of the 25 psychological attributes with the ‘impact supplement’ for 3 (and 4) year olds and 4–16-year-old children were used. Children’s symptoms which were suggestive of the child being a ‘case’ with mental health disorders were excluded, i.e., a score of above 17 on the total difficulties score.

Child and parent data collection tools:

General information schedule: This schedule was prepared for the study to obtain personal and family history of the child and other psycho-social information.

● Semi-structured interview schedule: This interview schedule was also prepared for the purpose of the study to obtain as many detailed anecdotal instances of common problem situations faced by parent/s following a broad ‘antecedent-Behaviour-consequence’ framework. Special attention was given to capture subtle nuances and details to make it appropriate for conversion into vignettes and screenplay.

● Parenting Stress Index- Short form (PSI/SF). [13] The PSI Short Form was developed by Abidin in 1986. This tool yields a ‘Total Stress’ score from three scales: Parental Distress (items signal parental distress coming from a variety of aspects of their experience), Parent-Child Dysfunctional Interaction (items indicate the degree to which the parent derives satisfaction from interaction with their child and how much the child meets their expectations), and Difficult Child (items here

are related to the child’s temperament). In the current study, this scale was used to understand the extent of parenting stress and to identify the sources of stress in terms of certain salient child characteristics, parent characteristics, and situations that are directly related to the role of being a parent.

Procedure:

Total of 40 parents were contacted. One dyad refused to participate due to difficulty in taking time out from their work schedules, and another dyad refused consent because the father did not perceive any difficulties in parenting their child and also, he did not consent his wife to take part in the study. Hence, only 36 parents (six father-mother dyads and 24 mothers) provided consent to participate. After mothers provided informed consent, every parent was met individually at a mutually convenient time and venue. The screening tools were administered. One father-mother dyad was excluded from the study because the score on SDQ was interpreted as ‘abnormal’. They were offered referral-related guidance for seeking professional help for the child.

The general information schedule and the questionnaires were administered to the final sample. Fathers were involved as informants in the semi-structured interview alone. This process took about 60 minutes with each mother/father-mother dyad. Qualitative analysis was carried out for the data collected in the semi-structured interview. This analysis led the researcher to choose which problem Behaviours were relevant to be converted into videos based on the frequency with which they were reported (those that appeared frequently were chosen). Antecedents and consequences pertaining to a specific problem Behaviour from all interviews were analyzed to see which situations best lent themselves to be video graphed. In this way, vignettes were prepared for each problem Behaviour in a ‘negative-positive’ format.

Video development stage:

The researcher underwent brief training in the technical aspects of videography at the “The Film making Course” at the Suchitra Cinema and Cultural Academy, Bangalore. Video development stage consists of video shooting, video editing and evaluation of the contents. Firstly, vignettes from the needs assessment stage were converted into formal screenplays. Potential parent-child actors were contacted. Those who provided informed consent and assent were recruited for

acting. The screenplay was handed over to actors and the videographer beforehand. Time and venue for the shooting were fixed based on the mutual convenience of all the parties involved (actors, videographer and researcher). The age of the child for any given video was decided by averaging the age of the children in whom the problem Behaviour was reported in the interviews. The actors were reassured that they didn’t have to memorize the dialogues. Parents and children

also volunteered with their own dialogues because they felt that the situation in the video was an 9 ‘every day event’ for them. They were free to do so as long as the dialogues corroborated with the message conveyed in the voice-over. The professional videographer recorded the play directed by the researcher and acted by the child and the adult actor in a home setting using the video shooting equipment. The video was then edited by the researcher and the videographer using an editing software. Each video took about 2 to 4 hours to shoot and 7-8 hours to edit.

Sample:

Parents and children conversant in English, with an ability to demonstrate some basic acting skills on request of the researcher (such as depicting sadness, repeating a line in an angry tone etc.) were included. A total of 11 child actors and 14 parent actors volunteered to act in the videos. Informed consent and assent were obtained from parent and child actors. Five parents reported reluctance to act and hence refused informed consent. It was assured to parents and

children that the videos will not reveal personal identifying information, if they wished so. Actors were informed that videos may be used in NIMHANS or at other professional centers such as schools or clinics for purposes of parent education.

Procedural details for Video development:

Screenplay: Every video developed in the study was guided by a screenplay. The structure of the formal screenplay and voice-overs was obtained from suggestions given in the book “Screenplay- Writing the Picture”. [14] The contents of the screenplay were based largely on an analysis of interviews with parents in the needs assessment sub-stage. Techniques offered in the ‘positive ‘interactions screenplays were derived from three sources: a) theory and literature on Behaviour modification and positive parenting, b) Indian research on parenting interventions, [10] and c) success experiences of the participant parents and inputs from the research guide.

● Video shooting equipment: Professional 1000 watts sun gun lighting, boom microphone and Panasonic HD camera were used to shoot the videos. The researcher benefitted from the expertise of a qualified videographer in this process.

● Editing software: The licensed version of the Avid Studio Toolkit version 5.7 software was used for the purpose of editing.

Video feedback form for experts: This form was prepared for the purpose of the study to evaluate the credibility and dependability of the videos developed. Following five questions were prepared:

o The video has two parts to it. What do you think is the basic difference between the two parts?

o Any suggestions for future videos?

o What are the techniques/suggestions that you noticed in this video?

o Did you feel that the techniques suggested are relevant to the problem Behaviour?

o What do you think is the problem Behaviour being addressed in this video?

Methodological rigour:

Across the two stages, efforts were made to establish methodological rigor. Following is a description of the concrete research actions taken to this end.

Credibility:

- Pilot phase was conducted to tune the ability of the researcher to obtain desired information in a manner that aided video development.

- During the process of interviewing, parents were prompted to elaborate antecedents and consequences of every problem Behaviour in detail. The researcher repeated and reframed the information collected in order to confirm the accuracy of her understanding.

- Triangulation was carried out in the information collected by means of inviting fathers to provide their version of the difficult parenting situations. 5 fathers were available during the interview. When mothers were the sole informants, they were requested to provide their understanding of what fathers and other members of the family felt/did in a given situation.

- There was prolonged contact (for about a month) maintained with some parents after

the interviews. This was done when parents were provided suggestions to handle some

of the problem Behaviours in their children. They were followed up by the researcher

every week over the telephone to enquire about the implementation and effectiveness of

the techniques suggested. They were also free to enlighten the researcher about any new

technique that helped them. This helped to increase the credibility of the techniques

suggested in the videos, basing them strongly on the feasibility in real-life. - Member checking was carried out, where the videos developed from the information obtained from particular parents were shown back to them. The parents confirmed an accurate representation of the information provided by them in the videos. It was also carried out as a part of the research audit trail, the elaboration of which is subsumed under the next sub-head.

Dependability:

Two independent raters blind to the researcher’s coding, coded a portion of the interview transcripts. There was high agreement amongst the three coders in the coding of problem Behaviour and techniques reported by the parents in the interviews.

- A research audit trail was presented to experts. The experts were a) one qualified child

psychiatrist with over 30 years of experience, b) one clinical psychologist and one

psychiatric social worker with over ten years of experience, c) two parents and d) one

primary school teacher and experienced parent. A powerpoint presentation was made to

each member individually, describing the research steps taken from the start of a

research project to the development and reporting of findings. Following this, they were

requested to randomly pick up three slips of paper consisting of a code denoting a video

(known only to the researcher). Each video starred children of different age groups i.e.

3-4 years, 5-6 years and 7-8 years. Each video was presented without the title. They

were free to request for any part of the video to be replayed, if needed. At the end of

every video, they were handed the video feedback form. All experts were able to

identify that the two major parts in each video were ‘negative’ and ‘positive’ ways of

handling a given Behaviour. The experts’ decision about the problem Behaviour being

addressed in all videos corroborated the intent of the videos. All experts were able to

note down techniques suggested. Modifications were suggested for the ‘Academics and

School’ video. These were incorporated by re-editing the video.

Analysis

Quantitative analysis:

Descriptive statistics namely frequencies, percentages, mean and standard

deviation were computed for data collected.

Qualitative analysis:

Inductive content analysis: [15] It was carried out for the semi-structured interview

data to help the researcher decide which problem Behaviours were relevant to be

converted into the videos (i.e., those with higher frequency were chosen). Analysis

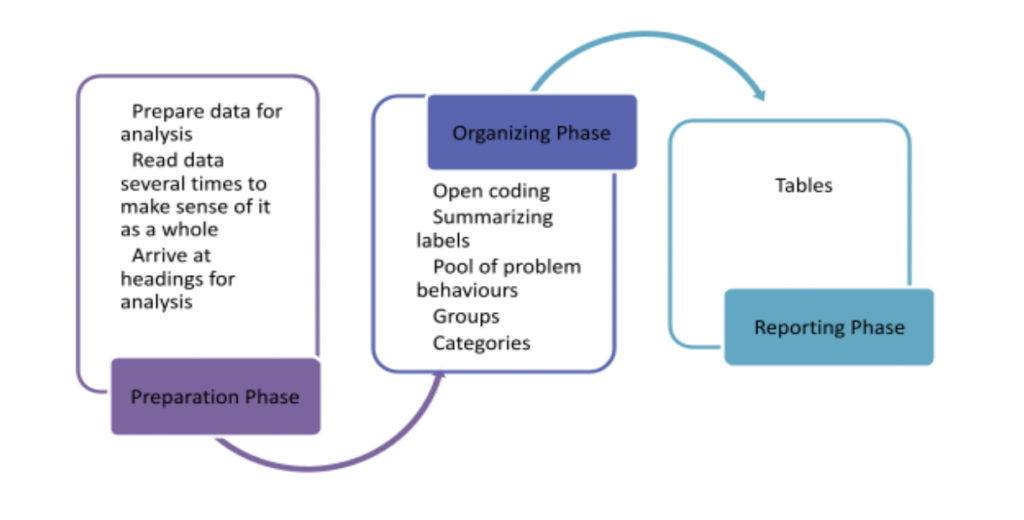

was conducted in three main phases: Given in Figure 1.

Results

Average age of the mothers was 32 years. 48% were graduates or diploma holders, and majority

of them were homemakers. 95% of mothers had no illnesses before, during or just after birth of

child, 5% had problems like low platelet count, diabetes mellitus and infertility. Average age of

the fathers was 37 years. 45% were graduates or diploma holders and majority of them were

managers or engineers or doctors. All families belonged to middle or higher SES.

Parental relationships and relationship of the primary caregiver with other family members were

cordial. 76% of mothers reported the presence of division of labor, while 24% of them reported

role-strain. There were no major medical or psychiatric illnesses in a large majority of the

families.

Of the 33 children, 58% were boys and 42% were girls. Sixty one percent of the children were

aged between 3-5 years, and the rest were between 6-8 years of age. All children were biological.

None of the children had any major illness soon after birth or at any time. Their developmental

milestones were age-appropriate. All children were predominantly satvik (easy) in their

temperament. All children, as per parents’ reports, had an overall secure pattern of attachment.

Despite overall secure patterns of attachment, favorable family conditions, and a dominant satvik

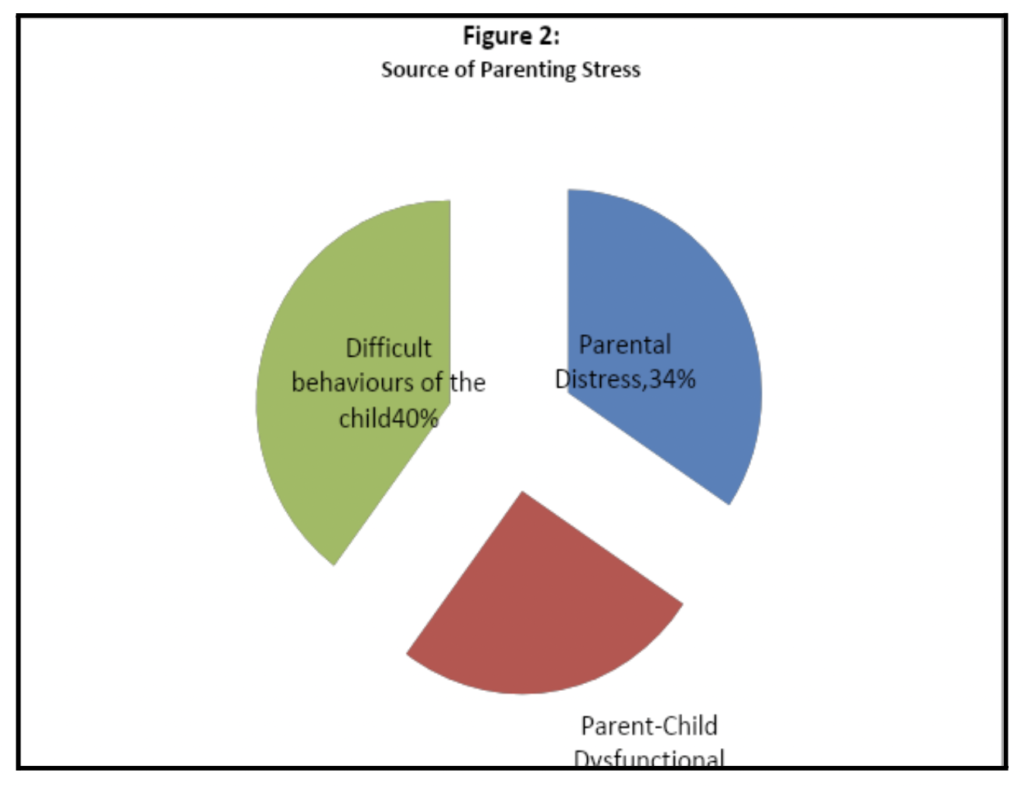

temperament, mothers reported moderate levels (45%) of stress in parenting in the Parenting

Stress Index. The pie chart (Figure 2) shows that a large amount of parental stress originated

from the difficult Behaviours of the child. This is substantiated by a high incidence of Behaviour

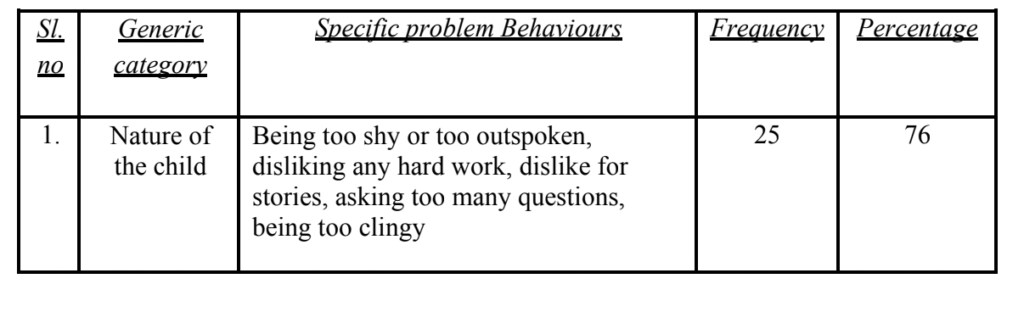

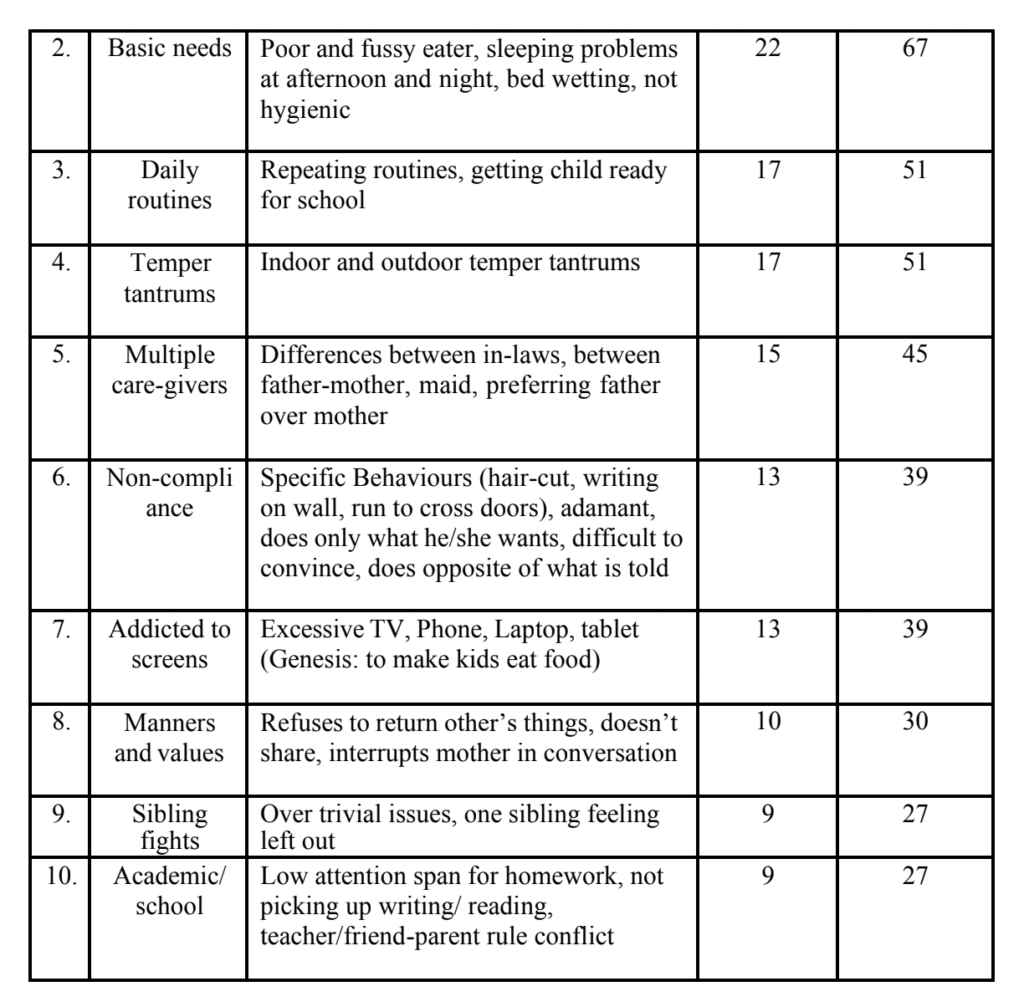

problems in their children. Table 1 illustrates the frequency and nature of child Behaviour

problems reported by parents in the interviews.

A total of fourteen videos were developed. The titles of the videos are Excessive Shyness,

Morning Routine, writing on the wall, Screen Addiction, Temper Tantrums, Fussy Eater,

Inconsistent Disciplining, Child too Clingy, Academics and School, Sibling Fights,

Disrespectful, Won’t Share, Outdoor Temper Tantrums and Parents & School. The development of NIMHANS parent training videos has thus made a small step towards attending to the lacunae on parenting intervention for urban middle, higher socio-economic strata. All the

videos are available on Youtube by typing the keyword “NIMHANS Parent training videos” in

the search area.

Evaluation of the study:

From a public health perspective, the video-based parent training programme can be

incorporated as a part of a preventive intervention for child Behaviour problems in the

community. This study has potential to pave the way for more controlled studies on the efficacy

& effectiveness of the use of videos in general medical, psychiatric & pediatric settings.

However, the limitation of the current study was that the actors in the video do not have expertise

on the visual arts. Further, the research audit trial was done only with the experts and not with

the parents. The expert feedback was sought based on only the content of the video and not on

the quality of the video/ audio, actor’s performance etc.

Conclusion:

This paper has two essential conclusions. First, even when all conditions seem favorable, there is

a felt-need for help with parenting their children among parents in the urban communities.

Second, the study has confirmed the feasibility of developing video material in the area of parent

training, which is not only promising, but also the need of the hour.

Figure 1. Process of inductive content analysis

Figure 2. Source of Parenting stress

Table 1. Shows the categories, sub-categories, frequency and percentage of difficult

Behaviours in children.

References

- Lewis V. Development and Handicap. Oxford, UK: Basil Blackwell. 2001.

- Hirisave U, Vasudevan M. A pilot study of promotion of psychological development and

mental health in early childhood using Psychovac Program. Unpublished project, NIMHANS,

Deemed University; 2007. - Flanagan S, Adams HE, & Forehand R. A comparison of four instructional techniques for

teaching parents to use time out. Behaviour Therapy 1979; (10): 94-102. - Nay RW. A systematic comparison of instructional techniques for parents. Behaviour Therapy

1976; (6): 14-21. - Dai YG, Brennan L, Como A, Lika JH, Mathieu TD, etal. A video parent training program for families of children with autism spectrum disorder in Albania. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rasd.2018.08.008.

- Bordini D, Paula CS, Cunha GR, Caetano SC, Bagaiolo LF, Ribeiro TC, etal. A randomized clinical pilot trial to test the effectiveness of parent training with video modeling to improve functioning and symptoms in children with autism spectrum disorders and intellectual disability. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1111/jir.12759.

- Hong ER, Gong L, Ganz JB, Neely L. Self-Paced and Video-Based Learning: Parent Training and Language Skills in Japanese Children with ASD. Exceptionalist Education International. https://doi.org/10.5206/eei.v28i2.7762.

- Stratton CW. The Incredible Years Program for children from infancy to Pre-adolescence: Prevention and Treatment of Behaviour Problems. Researchgate. 2010. DOI: 10.1007/978-1-4419-6297-3_5.

- Joseph M, Hirisave U, Subbakrishna DK. Mother-Child interaction in children with Behaviour problems- An observational study. NIMHANS Journal 2001; (19): 15-22.

- Poornima N. Efficacy of promotive intervention with lesser privileged preschoolers. PhD

thesis submitted to NIMHANS, Bangalore; 2007. - Sheehan DV, Lecrubier Y, Sheehan KH, Amorim P, Janavs J, Weiller E, Hergueta T, Baker R,

Dunbar GC. The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I.): The development

and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10.

Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 1998; (20): 22-33. - Goodman R. The extended version of the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire as a guide

to child psychiatric caseness and consequent burden. Journal of Child psychology and

Psychiatry 1997; (40): 791-801. - Abidin RR. Parenting Stress Index. 2nd Ed. Charlottesville: Pediatric Psychology Press; 1986.

- Russian RU, Robin U, Downs WM. Screenplay: Writing the Picture. 2nd Ed. Los Angeles:Silman-James Press; 2003.

- Elo S, Kyngäs H. The qualitative content analysis approach Research Methodology Journal of

Advanced Nursing 2007; 107-115.